The Rise of 88Rising (Tulanda Post #2)

88Rising is a record label and multimedia marketing group all rolled into one. The group was founded by Japanese-Korean American Sean Miyashiro and Chinese American Jaeson Ma in 2015.

The group was started by Miyashiro’s notice of “more Asian people creating damn good shit,” and figuring that it needed to be agglomerated somewhere. He credits “the beautiful Asian immigrant hustle” in himself and his parents to pushing him to work and build up the collective to where it is today (i-D).

The group features artists like Joji (Japanese-Australian), Rich Brian (Indonesian), and Keith Ape (South Korean) among others. Collaborations with the group often feature them singing/rapping in multiple languages, a clear association to who they are and their uncompromising nature on their background. Though they operate as independent artists, their newer work is all housed on the 88Rising YouTube page and they are often featured on the various 88Rising social media platforms.

Fitting with the new-age Millennial/Gen-Z audience that the company is going for, much of the 88Rising is on its social media itself, as opposed to a formal website. The only formal site associated with the group is 88NIGHTMARKET, which is primarily for merchandising but features the following blurb in their about section: “We grew up on the streets of night markets – from chinatowns to China towns and every Asian neighborhood in between.” (88NIGHTMARKET). This both directly embraces their Asian identities and credits it for its influence on the art that they now create.

The group is not very big on getting into the doors they are opening or how inspirational they may be for others, but they are definitely cognizant of it. “The unspoken truth that we know we’re doing something important, that we represent something great,” says Miyashiro (i-D). This understated approach to their impact reflects the removal of the burden of a culture and identity on them, and further solidifies them as artists creating their craft.

From collaborations with American artists, music festivals, and merchandise to popular channels and pages across all major social media platforms, 88Rising and the artists it highlights are going to be a cultural mainstay for years to come.

Dunn, Frankie. “88 Rising Are Starting A Global Music Revolution” i-D. Vice. 12 Nov 2018.

https://i-d.vice.com/en_uk/article/7x35qd/88-rising-joji-higher-brothers-rich-brian

https://www.instagram.com/88rising/

https://88nightmarket.com/pages/about

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZW5lIUz93q_aZIkJPAC0IQ

Asian Americans in Cartoons

In my childhood, cartoons were very popular. Which – I know – everybody watches cartoons in their youth. But for some reason, I have this inkling feeling (and it could just be projection) that cartoons are more important for millenials and gen-z than the generations that proceeded them. I mean, more content is being produced then ever from webtoons to 3D animated movies, on top of the fact that most of us grew up just after the boom of the Disney princess craze ensured lifelong servitude for many to the Disney name, to the extent that Disney+ is now exploding nationwide despite only housing one original series. My hunch is that cartoons were especially influential for my generation. In that sense, it’s interesting to look at cartoons as an aspect of cultural assimilation.

Because cartoons are targeted towards young children, there are definitely learning implications when depictions of race bound on stereotype. In this blog post I’d like to look at a couple examples of East and South Asian depictions of cartoon characters, and point out potential criticisms of them.

The lowest hanging fruit here for me is Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, from The Simpsons. Almost two years ago, the show-runners for Simpsons announced that they no longer had plans to include the character in future episodes of the show. The character was frequently criticized for being a negative stereotype of Indian culture, and it’s honestly not difficult to understand the criticism.

The problems mostly arose after a documentary featuring a handful of prominent Indian comedians and actors. The Simpsons released a response, in the form of Marge reading Lisa a bedtime story, and in order to keep it PC she had to keep struggling to change the details. The point supposedly is that we shouldn’t criticize characters and themes made over thirty years ago by the same standards that we criticize new things. The ending is sort of… ham fisted? It ends with a closeup on a photo of Apu which simply says “Don’t have a cow!” which many immediately took as a jab at hinduism.

On the flip side of things, the past twenty years have shown a rise to many positive role models for Asian Americans in cartoons. Saleah Blancaflor writing for NBC News made note of how many Asian American role models appeared in early 2000’s Nickelodeon cartoons. In particular, Saleah makes light of Phoebe Heyerdahl – the first Asian American character in nicktoons history. The focus of analysis however is on her father.

Her father, Mr. Hyunh is depicted in a interracial marriage. Hyunh is Vietnamese, and as such the Vietnam war actually plays a significant role in his background. English is not his language, but in the words of the show-runner, “Mr. Hyunh had a thick accent, but nobody on the show ever made fun of it and it was never a source of humor.” During the Hey, Arnold! Christmas special, he (and his daughter) gets an entire backstory.

I think, in several ways, these characters are very similar. They are both immigrants, with cultural backgrounds that dramatically inform their character traits and relationships to main cast members. They are both family men, and they both work blue collar jobs. The Simpsons show-runners even claim that to some Indians, Apu isn’t even a stereotype. However, I think largely any defense the show-runners create for Apu is retroactive. A character like Mr. Hyunh is created with love in mind. A character like Apu is made to be the butt of jokes.

I think in cartoons, all characters are a bit stereotypical. It’s the nature of the beast. To break something down into simple shades and shapes demands it. But that doesn’t mean that character and writing doesn’t demand nuance. And sure, maybe to some Indians Apu isn’t a stereotype. But that doesn’t mean that it’s okay to use race as the butt of a joke, at least when that joke isn’t being written by a member of that race. Even then, it could be difficult to defend. Luckily, I’d like to believe we’re moving away from that era of comedy, especially in children’s television.

Soren – Content Creator Freddie Wong

I chose to focus on YouTuber Freddie Wong for my “influencer” pick. Although he’s not necessarily an influencer, he had a huge role in the development of the early YouTube community, and was part of the wave of Asian content creators which saw meteoric rise. Freddie Wong was a huge part of my childhood, and I attribute many of his early videos to one of my greatest passions – visual effects! At the turn of the decade, Freddie Wong was a sort of beacon for low-to-no budget short films, which primarily were more akin to visual effects tests than anything else. For a young person however, it was exceedingly entertaining.

Freddie Wong was a graduate of USC’s Cinematic Arts program, where he met Brandon Laatch, who would eventually help him produce short films. A couple years into his YouTube career, Freddie made a video wherein a man gains extra height on a jump by firing a rocket at the ground. This was a reference to a popular glitch in the video game Halo. However, the video was a massive success, sporting a massive 24 million views today.

Freddie Wong’s success on YouTube led to a few things. First, he became the proprietor of three separate YouTube channels, the smallest of which had 2 million subscribers at its peak, the largest at 8 million. Secondly, in 2011 he and his college friend Brandon founded a production company known as RocketJump, named after their successful video. Wong garnered a great deal of attention after this and appeared alongside the likes of Jimmy Kimmel, Andy Whitfield, Kevin Pollak, Shenae Grimes, and Jon Favreau. Thirdly, RocketJump was responsible for one of the most quickly funded Kickstarter projects of all time, with their webseries titled Video Game High School. Originally funding was set at $75,000 for a 30 day period. By the end, over $270,000 had been raised. Video Game High School saw release the following year. The series had 3 seasons, and ended in 2014.

Sadly, Brandon and Freddie ended up having creative differences, and the production duo split in 2013. Wong continued to work on VGHS until the series end in 2014. Wong is now finding work in the podcast realm with two podcasts – in 2017 Story Break, and this year Dungeons and Daddies. His YouTube channel slowly has become less active until last year he stopped uploading entirely. Whether he plans to return to the space under the RocketJump name or otherwise remains to be seen. However, his influence on YouTuber’s such as Nigahiga and Wong Fu productions has been a permanent mark on the digital content creation space for Asian YouTubers.

Post #3: Whitewashing in Hollywood- Emmanuel Tuyishime

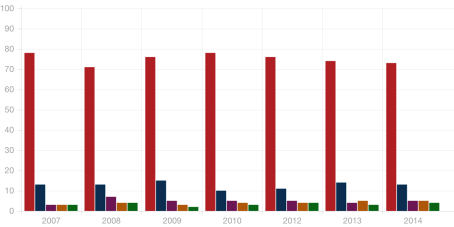

Red: White

Blue: Black

Purple: Asian

Orange: Hispanic

Green: Other

Graph representing race and ethnicity of actors/actresses cast in Hollywood from 2007 to 2014. Courtesy of PBS. (https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/30000-hollywood-film-characters-heres-many-werent-white)

Asians are cast more than 80% less than white people are. Surprisingly though, this does not necessarily mean that movies being produced don’t have Asian parts in them. These parts are usually given to white actors. Wikipedia reports 16 movies produced in the 21st century that have white actors playing asian roles. Even more recently in 2017, Scarlett Johansson was cast as Motoko Kusanagi in Ghost in the Shell.

What makes white washing in today’s Hollywood worse, I think, is the ironic position most of these stars take as progressive liberals and yet still engage in such activities. In the last two years, the film industry has been labeled progressive, especially with the rise of female actresses (equal pay & the MeToo movement). It is deeply sad that these same people can endorse and participate in the continued marginalization of Asian and other People of color actors/actresses.

Sources for more information and reading:

(https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/30000-hollywood-film-characters-heres-many-werent-white)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Examples_of_yellowface

Social Media Post: Timothy DeLaGhetto-Emmanuel Tuyishime

Tim Chantarangsu, born from parents of asian heritage is a Youtuber, rapper and Instagram influencer. He is mostly known from the comedy roast show, Wild’n Out. Tim has 1.5M instagram followers, 4.7M Youtube subscribers and 571K Twitter followers. Apart from rapping, Tim also does comedy videos on Youtube mostly about Asian Culture.

On Wild’n Out, Timothy has been criticized of embracing stereotypical asian jokes, but many have also come to his defense stating that those jokes are part of the show and are not in any way harmful to the larger Asian American community.

Timothy and other small scale influencers like him are who Kido Lopez attributes the ability of Asian American to cross into mainstream media to. Tim himself, has had an interesting journey as far becoming a mainstream influencer is concerned. He recently has been featured in shows with more prominent celebrities, and is also able to attract buzz from his youtube interviews of other celebrities.

Timothy’s Youtube, though meant for comedy is also very educational. He makes videos about Asian American culture that are able to resonate with all races and gunner millions of views. He tackles topics such as dating, food, and race & cultural appropriation. Tim currently has over 800M views on his channel. Here are some videos that could be considered both comedic and educational:

How Square-Enix’s Sleeping Dogs Opens The Door For Ethno Communications Games

I grew up on video games. From first grade until the end of high school, I would come home from school virtually every day and play video games for at least an hour. They’ve always entertained me, and even have facilitated my learning. I like to joke that video games taught me how to read. Towards the end of young adulthood gaming stretched into sessions of three to four hours straight, with six to seven hour marathons on weekends. Predominantly, I grew up playing single player adventure games. Legend of Zelda, a handful of Japanese Role Playing Games (known colloquially as JRPGs), as well as Skyrim, Fallout, and Fable to name a few European and American releases. I’ve gravitated towards this style of game because it gives the player a degree of freedom in comparison to games like Mario or Tetris. For example, most games of this fashion feature character creation interfaces where you can design the appearance and proficiency of your character. Other single player adventure games do not allow this sort of freedom. For example, Red Dead Redemption decides that you will play as John Marston, ex-outlaw turned rancher. The common thread however, is that more often than not there is only a loose goal that you may choose to pursue or not. Otherwise it’s just you and an interactive virtual sandbox so to speak.

Sandbox Gameplay:

As I’ve grown older and more cognizant of all sorts of social narratives, I try to note now when I play these games what it means to take that choice away. In Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed 3, you play as an indigenous American in line with colonial American forces during the civil war. All sorts of ethical questions arise from this sort of game. For example – what does it mean for me as a Caucasian man to control the actions of this protagonist? As The Video Game Studies Reader more clearly states – “computer games are not ‘just games’ but play a constitutive role in our cognitive development and in the construction of our identity … You have to do more than identify with a character on the screen. You must act for it.” (Wolf 933) Throughout the course of this class, my eyes have been opened not only to representation of race, but representation of place and class in relation to race. However, the realm of action and reaction complicates the relationship of the viewer with the subject of their gaze. For this blog post, I’ll specifically be examining Square-Enix’s Sleeping Dogs (2012).

Sleeping Dogs is a fascinating inclusion in the single player open-world crime sandbox genre, because it’s not just one of the only games in the genre featuring an (almost) all Asian cast, but to my knowledge it’s the only game of its genre which takes place outside of the United States. Occasionally referred to and marketed as “Asian Grand Theft Auto”, the game entirely takes place in Hong Kong and revolves around Asian American protagonist Wei Shen.

Asian Grand Theft Auto:

Before the events of the game, the player learns through in-game dialogue that Shen’s sister, Mimi, becomes addicted to drugs. She gets involved with triad activity in Hong Kong before their family moves to San Francisco, where Wei Shen becomes a documented U.S. citizen. After graduating from San Francisco College, Shen enrolls in the SFPD and graduates in the top of his class. He becomes notorious in the SFPD for his meticulous and thorough (albeit violent) execution of undercover operations, catching the eye of Hong Kong Police Superintendent Thomas Pendrew. The game starts after Wei Shen is hired by Pendrew to infiltrate the Sun On Yee (新安義), a triad group riffing off the real life Sun Yee On gang (新義安). Shen takes the job, but in a classic turn of events, becomes too invested in the gang after a civil war between the heads of the Sun On Yee territories breaks loose. The game features an impressive cast, enlisting the voices of actors such as Lucy Liu, Emma Stone, James Hong, Elizabeth Sung, Ron Yuan, Tzi Ma, Will Yun Lee, and Chin Han. The large majority of Hongkonger characters in the story are faithfully represented by voice actors who live or have lived in Hong Kong. There are no Asian characters played by non-Asian voice actors. Furthermore, there are less than a handful of white characters in the story barring a Russian bartender, an American tourist named Amanda (Emma Stone), and Superintendent Pendrew (Tom Wilkinson).

Sleeping Dogs Trailer (Warning: VERY graphic):

While on the surface Sleeping Dogs is a violent crime game that one could argue represents Hong Kong and Chinese Americans in a negative light, it also offers a unique insight into the experience of Asian American immigrants who move back to their homeland from the United States, and thus struggle with a loss of identity. Through various cultural references, the character arc of Wei Shen, and a large allowance of player agency, Sleeping Dogs opens the door to an exploration of Asian identity perhaps to an even greater depth than many Ethno Communications Films could.

Firstly, let’s make no mistake about it that Sleeping Dogs is not a perfect picture of representation for Asian American men. In the introduction post I make a point that games like this have the potential to explore identity better than Ethno Communication Films but it’s important to recognize that unlike many if not all of those films, Sleeping Dogs is ultimately a project directed and produced by non-Asians. In this way, Sleeping Dogs presents in a very real sense some idea of “Techno-Orientalism.” Here’s a behind the scenes video for the production of the game.

Sleeping Dogs Behind The Scenes:

If you watch the video, you’ll notice that not a single Asian voice speaks. The Executive Director Stephen Van Der Mescht claims at the start of the video that they were inspired to make the game after watching Hong Kong action flicks. He states “For us it made perfect sense to bring the action, you know, to bring an open world game, to somewhere that gamers have never been before.” Meanwhile, the Senior Producer Jeff O’Connell states immediately after, “You have the crazy extremes, and the crazy characters just there for your… your enjoyment.” So there is certainly a degree of spectacle, a degree of exoticism involved with the choice of setting and characters. To take the most sensitive aspects of a culture — its gangs, economics, police relations, colonial history — and to make a show out of it is not unlike something such as Flower Drum Song, which seeks to make a spectacle out of San Francisco’s Chinatown. In Filming “Chinatown”: Fake Visions, Bodily Transformations, Sabine Haenni theorizes that “production and consumption of Chinatown may assert a white hegemony, even as it grants its viewers access to new, rather than old, mobile, rather than static, subjectivities.” (Haenni 23) Haenni continues, quoting Sigfried Kracauer. “…[the human spirit] squats as a fake Chinaman in a fake opium den, transforms itself into a trained dog that performs ludicrously clever tricks to please a film diva, gathers up into a storm among towering mountain peaks, and turns into both a circus artist and a lion at the same time….” Haenni argues following this that Chinatown films allowed white spectators to “pleasurably experience the newly racialized metropolis by consolidating a new kind of white hegemony, and by assigning the Chinese to a constrained space.”(25)

It could be argued that Sleeping Dogs choice of setting and characters is the digital and modern manifestation of this idea. The protagonist is a kung-fu master, who largely avoids using guns at all. Had the game been about a white, black, or latinx cop in America, or any other country, my instincts tell me that the game probably wouldn’t have involved a huge degree of kung-fu. However, while it’s true that the narrative and place are merely digital representations from the perspective of white outsiders, it’s also true that these representations are not based on observation, but on first-hand account from Hong Kong locals. In the same behind-the-scenes video above, O’Connell claims “Watching movies wasn’t enough, reading books… wasn’t enough…. We were really lucky to be able to talk to people on both sides, the police, and the triads.” O’Connell continues to describe the stories they were told by the natives of Hong Kong explaining the structure of daily life, and the experience of spending a day with triad members. To the credit of the white men at the helm, the characters and narratives told in the story of Sleeping Dogs are not merely white imaginings of Chinese characters, but largely researched and based on oral storytelling. Although the story is ultimately being crafted and curated by white men (who definitely have their own agenda), this pushes Sleeping Dogs a lot closer towards films like Chan Is Missing, rather than Year of The Dragon, or Flower Drum Song. This is because, in a certain sense, there is a Chinese voice in the narrative of this game. It’s a game that wants to play like a Hong Kong action movie, with an Asian American protagonist who loses touch with his Hong Kong roots. Because of its authentic focus on identity, oral accounts of life from Hong Kong natives, and almost entirely native cast of voice actors, I think it’s only fair to say that while Sleeping Dogs is not a perfect representation of Asian American men, it is still a respectful and well researched one, which takes care to avoid surface level stereotypes.

Beyond an extreme appreciation and in-depth research of culture and daily life, Wei Shen is also an interesting protagonist who in my opinion fits much better into the world of Chan Is Missing than Year of The Dragon and maybe even some of the action films his character derives from. The first fascinating aspect of Shen’s identity how he is represented sexually. As part of a side-narrative in the story, you can optionally choose to find and date women. In terms of gameplay this means wait until a woman is introduced to you and then take on an optional task which results usually in the screen going dark as Shen and the woman either go to her apartment or agree to meet up another time. The first woman Shen meets is a white woman named Amanda. Amanda claims to be an American post-graduate exploring Hong Kong, but after Shen takes her on a date he discovers that she is just a gold digger who’s obsessed with Chinese men and taking advantage of Shen. This is an interesting role reversal with regard to Marchetti’s concept of “Rape Fantasy.” With regard to Broken Blossoms, Marchetti writes, “The specifics of Cheng Huan’s Chinese ethnicity and racial difference simply adds a veneer of exoticism to Broken Blossoms, encouraging a familiar fantasy of Asia as feminine, passive, carnal, and perversive.” (Marchetti 44) Amanda, in the narrative of Sleeping Dogs, by contrast serves maybe an opposite purpose in two ways. The first is that Amanda is one of the sole representatives of white America in the game. She is not “feminine” nor is she “passive”, but she is carnal, and perverse. Secondly, Shen establishes that he will not be used by Amanda or any white woman solely on the basis of race, and he cuts ties with her. Shen is also not feminine or passive, but clearly the objective for Shen is not sex, otherwise he could have been happy submitting himself to Amanda despite knowing her motivations. Primarily, while sex is a motivation for Shen, he is not sexually objectified in the same way that Cheng Huan is. He has sex with Amanda once after their date, and never again once he learns she’s met up with several other successful Chinese men. Shen proceeds to only date Chinese women for the rest of the game, each of whom reacquaints him with Hong Kong nightlife and culture. There appears to be symbolism here for Shen, who turns away from American sexualization of Asian bodies, which directly counters the representation Asian men in Marchetti’s Rape Fantasy.

Furthermore, throughout the story there is an ongoing self-conflict for Shen between embracing the values of the Sun On Yee or the values of the San Francisco and Hong Kong Police Forces. Shen must decide throughout the course of the game whether he should sell out his friends in the Sun On Yee, or whether to ignore orders from Superintendent Pendrew. It comes to a conclusion after Pendrew sets up a fight between the rival gang 18k and the Sun On Yee. Pendrew is caught on camera murdering the bedridden head of the Sun On Yee, Uncle Po, and after that evidence comes to light (and after a dramatically gore-filled chain of events), Pendrew is ultimately brought to justice and arrested by Shen on charges of corruption and collusion with the triads. Shen then not only stays on good terms with the gang of his youth, but also maintains his position in the Hong Kong police force. The ending feels a bit rushed, but Wei Shen’s last words are “strange to say it after all that’s happened, but Hong Kong kind of feels like home.” His colleague then cryptically states “But which Hong Kong officer?” Her line is followed by a high ranking member of the Sun On Yee observing their exchange from a limousine. The implication seems to be that although Shen doesn’t definitely pick a side, both sides in some form or another have allegiance to Shen, and are satisfied with his current position. Shen seems to feel that he finally has a place in Hong Kong, even though that place is ambiguous. This to me felt reminiscent of the ending monologue in Chan Is Missing, which details several accounts of Chan Hung, creating ultimately a vague vision of a centralized identity for Asian American men. Much like Chan, Shen’s identity remains ambiguous, however perhaps his identity relies on the ambiguity itself.

Ending Scene of Sleeping Dogs:

Finally, I’d like to briefly discuss what player agency means when the protagonist might represent a different race or culture, and how it opens the door for a wider exploration of immigrant and minority identity than film might be capable of. On race and identity in games, The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies states, “Games, like cultural modalities before them, help render and standardize historic racial myths as it does myths and discourses of the body.” It continues, “Identification with games might be more intense than in the case of narratives… .“ (Wolf 934) The reason games like Sleeping Dogs are important is not just because they inform players about the identity of the main character. Any type of narrative experience could do that. However, what gaming allows (and specifically open world gaming) is the creation of experience in the shoes of the other. Games allow worlds to be explored, and interacted with. The motivation of the character and the motivation of the player becomes unified. With that power comes great danger, since it relies on respectable representations of race. So, potentially if there were a movement of Asian American storytellers, much like with the Ethno Communication Films, who could deliver honest explorations of identity through gaming — it could be huge for changing and controlling cultural interpretations of Asian Americans the world over.

While Sleeping Dogs certainly has a plenitude of flaws, the detail of research, the care given to representation of Asian American identity, and the potential for player agency to change the interpretation of that identity all set the stage for something larger. Its greatest flaw is that it establishes itself as a kung-fu game, which results in all manner of crazy silly fight scenes. As a saving grace however, at least the motion capture they used was from real kung-fu martial artists. The next step is for more game developers to take a chance on letting immigrants and minorities take control over their narratives, when the story concerns their lives. Or even, potentially for groups of Asian American game developers and writers to form, and to strive to take control of the gaming narratives themselves.

Related Texts:

Haenni, Sabine. “Filming ‘Chinatown’: Fake Visions, Bodily Transformations.” Screening Asian Americans, by Peter X. Feng, Rutgers University Press, 2002, pp. 21–50.

Marchetti, Gina. Romance and the “Yellow Peril” Race, Sex, and Discursive Strategies in Hollywood Fiction. Univ. of California Press, 1993.

Wolf, Mark J. P., and Bernard Perron. The Routledge Companion to Video Game Studies. Routledge, 2016.

Asian American Experiences of Beauty Standards: Yasamin (3/3)

by Emma Li

In First Generation, the contrast between My-Linh’s new orange-haired appearance and her black hair dye drenched montage at the end emphasizes the dichotomy of beauty standards. My-Linh either changes her appearance according to white-washed standards or she imagines the destruction of these standards. Either way, the film sets societal standards as the ultimate determining factor. In the short Yasamin (2018) directed by Julia Elihu and Ashton Tu, the protagonist is a young Iranian girl named Yasamin living in the US during the Iran hostage crisis. Throughout the film, she also struggles with the disjuncture between her family’s culture’s beauty standards and those of her American peers. The point of contention is the hair connecting her eyebrows. Although Yasamin also ends up changing her appearance to assimilate, the short ultimately reaches a different conclusion compared to First Generation, as Yasamin’s mother sets the individual as the ultimate determining factor, rather than societal standards.

When Yasamin opens up to her mother about other kids in class making fun of her unibrow, her mother shares a story of her own teenage struggle with appearance. She tells Yasamin, “So you have a little hair. It’s no big deal. Without hair, with it, you’re pretty. Don’t worry. Don’t let people’s words bother you. Don’t pay attention. I promise you everything will get better.” This seems to reassure Yasamin as she smiles back at her mother. Unlike First Generation, the rhetoric presented in Yasamin is that we need to feel comfortable in our own skin regardless of our appearance.

While First Generation compiles shots of advertisements to point out white-washed American beauty standards, Yasamin includes montages of Iranian art to represent traditional Iranian beauty standards that praised unibrows. When Yasamin reveals her waxed eyebrows to her mother, the scene cuts to three shots of art depicting people with unibrows dressed in colorful traditional clothes. Their appearance “is clearly at odds with typical white-washed representations of royal, wealthy, attractive Middle Eastern women” (Vice).

According to a Vice article and Iranian-born Harvard professor Afsaneh Najmabadi, “under Iran’s Qajar dynasty (1785–1925), beauty ideals shifted under Iran’s Qajar dynasty and the female unibrow had a defining moment. . . . Women wore thick, dark eyebrows and mustaches, sometimes even enhancing the hair on their upper lip with mascara.” Although Yasamin did not fight with her mother over her eyebrows, Yasamin’s initial unwillingness to reveal her waxed brows and her mother’s initial response suggest that “hair removal is still a contentious subject among some Iranian parents and their teenage daughters living in the West because of this legacy” (Vice).

Living in the West poses various challenges to mothers like Yasamin’s who advise their daughters to not let other people’s words bother them. Immediately after this conversation between Yasamin and her mother, the very next scene shows Yasamin and her cousin facing racist remarks on the school bus from their peers. They’re told to “go home” and “don’t take us hostage” as crumpled up paper balls are thrown at them. Yasamin tries to cheer her cousin up with an inside joke, but the reality remains that their everyday life is heavily impacted by public perceptions of Iranians and unibrows. While Yasamin is able to find comfort in her family and chuckles in the face of adversity, the film ends on the hardly escapable reality of immigrants growing up in an anti-immigrant environment.

Through the mother’s words, Yasamin provides some hope for young Asians struggling with American beauty standards. Nonetheless, it does not shy away from representing the beauty and identity struggles faced by the Iranian characters. The short actually begins with a television news anchor discussing the Iran hostage crisis and Yasamin’s mother commenting on the constant broadcast of the crisis. The mainstream media shapes the public perception of Iranians and influences Yasamin’s classmates to harass her. Similarly, in First Generation, the faces that air on television and get printed in magazines shape societal beauty standards and influences My-Linh’s own self-image. Both films address the nature of mainstream media in shaping beauty standards and how Asian characteristics are judged. As an Asian American, I experience the products of these media discourses in my everyday life. However, with new developments in the Asian American mediascape, media objects like Yasamin and First Generation also have great potential to reshape societal beauty standards and the conversations about those standards.

(All images’ source: Yasamin)

Click here to view the first post in this series.

Mississippi Masala: Gaining Control over one’s Multi-ethnic identity – Hugo Anaya (3/3)

Ugandan native, Mina, embodies the cultural shift of women gaining control in media which allows her to depict a freshly new, and often ignored, perspective of cross culture representation. In Sarah Krakoff’s Film Review/Essay Media Masala: Why Women’s Control Matters, Krakoff argues that the media has a huge amount of power and influence in the shaping of perspective in media. Therefore, as women begin to gain control in the various aspects of media, whether that be on or off the screen, there begins to be a shift in perspective that is provided to its viewers and to a larger extent, societal norms[1]. Directed by Mira Nair, Mississippi Masala tells the forbidden love story between Asian Americans and Indian Americans as it attempts to depict the commonly ignored perspective of mix cultural identity. In the film, Mina (Sarita Choudhury), daughter of Jay and his wife, Kinnu, are forcefully removed from their home in Kampala, Uganda as a result of a 1972 policy enacted by dictator Idi Amin that kicked out all Asians from Uganda. As a consequence, the family relocated to Greenwood, Mississippi, where the young family reunite with family members who owned a motel chain. As a result of her growing up in the United States, Mina had an easier time embracing their new lifestyle and assimilating to the American culture. As a by-product of her Ugandan-Indian roots and American upbringings, we get to see a lot of moments in which Mina rejects the cultural expectations she is burden by her parents and community therefore gaining control over the life choices she makes throughout the film. One such instance is when Mina exercises control over her romantic life. Instead of taking the ideal suitor, Harry Patel, from her ethnic group, she chooses Demetrius, an African American carpet cleaner as her romantic choice. In making this decision, the audience gets to peer through the lens of an interracial couple experiencing the awkward and sometimes hostile interactions in the South instead of the often common visual of intermingling between Indian couples who are a product of their culture’s arraigned marriage customs. Therefore, as Mina begins to exercise more of her control from her multi-cultural identity, the audience gets to experience new perspectives that are often hidden or ignored in media and society.

Director Mira Nair uses the interracial romance between self-employed carpet cleaner Demetrius (Denzel Washington) and hotel maid Mina to explore the intricate relationship between multi-cultural identity, diasporism and home. Hamid Naficy’s Multiplicity and Multiplexing in Today’s cinema: Diasporic Cinema, Art Cinema, and Mainstream Cinema article explores the resurgence of a new mainstream cinema, in which she calls it “multiplex cinema”. This new form of cinema exists in a post-diasporic and post-Internet globalization world helmed by the multicultural and physically displaced filmmakers who are the leading voice in this new form of cinema[2]. According to Naficy, “As a result of their displacement from the margin to the centres, they have become subjects in world history; they have earned the right to speak and have dared to capture the means of representation” (Naficy 14)[3]. As a result, Naficy that the “multiplex cinema” we are seeing today represents the experiences, perspectives and visualization of a displaced group of people. Similar to the filmmakers, Mina is displaced from her home. Being of Indian descent but, born in Uganda, she experiences three forms of displacement throughout her life. Being born in Uganda with Indian descent illustrates the very first time in which Mina is displaced. In this instance, and throughout the film, we are reminded that although Mina may celebrate and exercise customs from her ethnic community, she has never actually been to India herself. Concurrently, the very same customs and practices that Mina and her family perform are the reason she is displaced, a second time, from her home country of Uganda, forcing her and her family to relocate somewhere else. Fast forward to the present day in the film, Mina lives in the United States alongside a small Indian community in the south. While her ethnic identity has followed her from Uganda, her American upbringing allows her to easily assimilate into the culture. However, in doing so we begin to see a mixture between both of her identities. We see this in the bar seen between Harry Patel and Mina where Mina’s family ethnic ties are the reason she shows up at the bar in the first place, yet due to the familiar ties with American hangout culture results in Mina being comfortable enough to stay at the bar whereas Harry Patel promptly leaves. While Mina has become much more comfortable with her life in American, the same can’t be said about her community. Her parents, in particularly her father, views their time in the US as a passing period in which he believes he will be able to go back to Uganda and continue his life there. Her community, a displaced group of Indians in Greenwood Mississippi, still heavily follows their traditions. Her date to the bar, Harry Patel is a suitable taker for her hand in marriage in her ethnic group. However, her diverse upbringing allows her to choose her romantic relationship with African American Demetrius. Her relationship with Demetrius is not received well, especially from her father who dislikes black people due to their involvement in him being kicked out of Uganda. Therefore, Mina and Demetrius are forced to leave their homes in order to pursue a love that is otherwise not received well in the Indian community. Similar to the filmmakers in Naficy’s article, Mina’s past in her diasporic Indian community and displacement from Uganda allows her to build a multicultural identity that displays the emergence of her control and voice.

[1] Krakoff, Sarah. Film Review/Essay Media Masala: Why Women’s Control Matters. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California.

[2] Hamid Naficy (2010) Multiplicity and multiplexing in today’s cinemas: Diasporic cinema, art cinema, and mainstream cinema, Journal of Media Practice, 11:1, 11-20

[3] Hamid Naficy (2010) Multiplicity and multiplexing in today’s cinemas: Diasporic cinema, art cinema, and mainstream cinema, Journal of Media Practice, 11:1, 14

Asian American Representation in Crazy Rich Asians (Alissa Final)

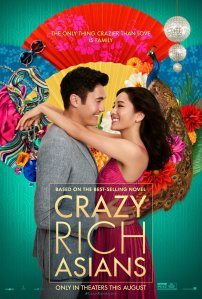

The rise of television and film has drastically interwoven into the American lifestyle, and as popular culture converges with the political atmosphere of the United States, it functions as a tool for expression and reform. Crazy Rich Asians were based on Kevin Kwan’s 2013 best-selling novel and take much inspiration from the writer’s privileged upbringing in Singapore. Crazy Rich Asians was released in 2018 and raked in around $238 million at the box office. Additionally, Crazy Rich Asians has been the first predominantly Asian cast in a big-budget Hollywood movie in about 25 years.

We have seen time and time again the misrepresentation and underrepresentation of Asian Americans in cinema. However, unlike many of the films we have watched throughout the semester, this could be one of the first films that are void of popular Hollywood stereotypes such as “dragon lady”, “lotus blossom”, along with many others. Rather, Crazy Rich Asians depict Asian Americans as multidimensional people with different experiences and backgrounds. Additionally, it represents the many contrasting Asian women’s experiences across generations.

The movie, Crazy Rich Asians follow the story of a girl named Rachel Chu (Constance Wu) who is a Chinese-American professor. She quickly falls in love with a man named Nick Young (Henry Golding) who is from an incredibly rich Singaporean family. Although Rachel does not know this at first, when she finally meets Nick’s rich family, she struggles with feeling accepted as well as trying to hold on to her own identity while trying to navigate herself in such an unfamiliar world. While watching this movie, I found myself relating to Rachel Chu’s experience SO much for what seemed like the first time ever. Although I have seen multiple Asian Americans in some form of media before, I never felt like my identity aligned with theirs, except for our shared heritage. Like Rachel Chu, I have been called a “banana” before which refers to someone being “yellow on the outside and white on the inside” or in other words, an Asian-American who has lost their “Asian” roots. Being a Chinese American adoptee and growing up in America for pretty much my whole life in a white family, I have missed out on ever celebrating “Asian” holidays, eating Chinese food, knowing and understanding Chinese cultural traditions and norms, and not even being able to speak Chinese. Therefore, I always feel the need to prove that I am “Asian enough”. The storyline, as Constance Wu has stated shows, “[Asian] culture is more than skin deep”, meaning that although a majority of the characters in this movie share the same heritage, their experiences differ from each other. This is so powerful as it truly depicts Asian Americans as multidimensional people.

There is a scene of the movie that I remember so distinctly. The moment was shared between Rachel Chu and Nicks’s mother, Eleanor Young, while playing a game of Mahjong where Eleanor tells Rachel that, no matter what, in the world of Singapore high society, Rachel will always be a foreigner. To Eleanor, Rachel is not part of her, “own kind of people” because she is American and all Americans can think about is “their own happiness”. However, through the careful playing of Mahjong, this game becomes an analogy of their life’s struggle and values. During this game, Rachel could easily win but decides not to, to let Eleanor win instead. While she lets Eleanor win, she tells her that she turned down Nick’s proposal to her regardless of the fact that she loved him. This was due to her wanting to put Nick first and save more potential conflict between Nick and his family. This shows that regardless of Eleanor’s accusations that since Rachel is more American, she must not think about anyone except for herself, Rachel is proving that not only is she wrong, but she’s done seeking Eleanor’s approval. She has finally accepted herself and her identity. During the shooting for this scene, Constance Wu actually found herself very emotional as she could she identify with many of the feelings that her character, Rachel was feeling in this scene. The fact that Constance could draw from her own experiences and feelings while portraying this character in a Hollywood movie is so powerful.

https://www.cnbc.com/2018/08/15/crazy-rich-asians-star-constance-wu-was-once-in-deep-debt.html

It is impossible to encapsulate the richness and complexities of the Asian diaspora through just a single movie but Crazy Rich Asians attempt to. The main aspect of the Asian American experience presented in the movie is one that many can still identify and relate to: that one is constantly straddling two cultures, always afraid that they are unable to fully immerse into a single one. By representing the struggle, the movie shows and acknowledges Asian Americans as encompassing varied complex identities, rather than being a flat character with little individuality or personal development. Additionally, Crazy Rich Asians have most importantly proven to society that Asian American centered stories can live in media today. This ignites the possibility and hopes for more Asian and Asian American representation, leading to a more holistic understanding of what “Asian American” identities consist of.

Beck, Lia. “How ‘Crazy Rich Asians’ Co-Writer Adele Lim Changed The Story To Make The Women Even Stronger.” Bustle, http://www.bustle.com/p/how-crazy-rich-asians-co-writer-adele-lim-changed-the-story-to-make-the-women-even-stronger-10160198.

Chow, Andrew R., and Ang Li. “How Hollywood Is Faring One Year After Crazy Rich Asians.” Time, Time, 10 July 2019, time.com/5622913/asian-american-representation-hollywood

Ho, Karen K. “How Crazy Rich Asians Is Going to Change Hollywood.” Time, Time, 15 Aug. 2018, time.com/longform/crazy-rich-asians

Social Media Influencer: Lilly Singh – Karen Song (Post #3)

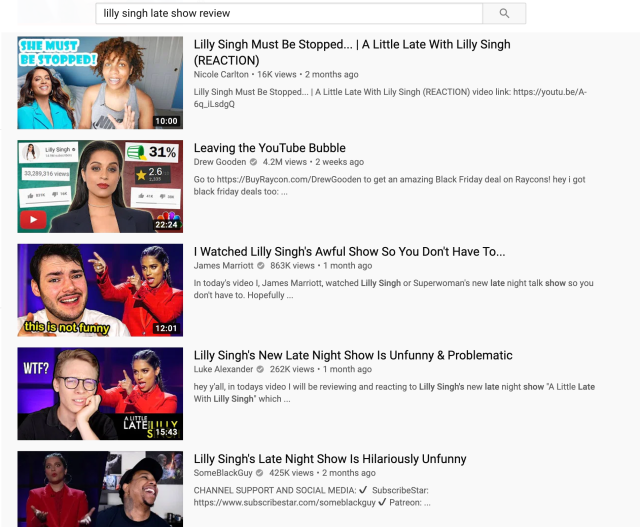

Lilly Singh is a Canadian influencer and comedian who gained immense popularity as a Youtuber with her channel IISuperwomanII. Her fanbase of younger viewers, including myself, quickly grew as she rose to fame with her relatable personality and parodic videos. She gained popularity for her distinct voice and commentary on her Indian heritage, and in 2017, she became one of the top 10 highest paid influencers on the platform. This all changed in March 2019, when NBC announced that she would be hosting their new late night talk show: A Little Late with Lilly Singh. Although much of the shift in her public persona and perception can be attributed to the stark contrast in the two platforms – one being an independent Youtube channel, and the other being a program on a major American channel – viewers soon began to individually criticize her for adopting a new voice that only served to appease network television’s superficial desire for greater diversity. Below, I’ve attached a screenshot of the first page of results that appear when you search for “Lilly Singh Late Show Review” on Youtube today.

The response is stunningly negative, with some stating that she is simply not funny or skilled enough to take on the mantle of a late night talk show host, and others diving deeper into her behavior which propels a “problematic” liberal agenda. What’s worth noting here is how the critique comes from all angles, including her fans and people of intersecting minority groups as well as those who feel attacked by her extreme stance against cis-het white men. Much of the issue that audiences have lies in how she has constructed her host personality around her identity as a bisexual woman of color and participates in what some have called “oppression olympics,” wherein she continuously emphasizes how she is less privileged than her competitors as a primary marketing strategy. Before the show premiered, promo videos began to circulate the internet which mostly consisted of her stating that she was the first person of color or LGBTQ identifying host of a talk show, which in turn led people to comment on how she ignored the revolutionary work of Oprah Winfrey or Ellen DeGeneres. This all begs the question, how has Lilly Singh and her new show contributed to the state of Asian American representation today?

In her text in The Routledge Companion to Asian American Media, Professor Kido Lopez discusses how Asian Americans have often only been able to break into the mainstream through depictions of “violent heteromasculinity and bourgeois materialism,” though they can also exaggerate these qualities in a satirical manner to “remind viewers that Asian American bodies are so often denied access to these kinds of roles” (Lopez, 163). In this same vein, Lilly Singh has tried to challenge the hegemonic norms of late night television by performing a hypermasculine archetype in the name of parodic comedy. Though her aim is clear – to subvert the dominant narrative and characters seen on late night TV whilst emphasizing her distinct minority status – the execution of this vision has further alienated audiences, both progressive and conservative. We see this in the cold open of her first ever episode, wherein she goes to extreme lengths to show how she stands out from the cis-het white men who dominate network and cable late night talk shows. In the intro, she asserts that she is different from all the “Jimmy”s (referencing Jimmy Fallon, Jimmy Kimmel, and James Corden), whilst wearing a power suit, showering the table with cash, and exhibiting power through violence (swinging a bat, kicking her white coworkers out of their seats, and throwing shoes at them). She does this all through a rap performance and music video – which also elucidates another common criticism that people have about her use of AAVE and appropriation of Black culture. All of this goes to show how her distinct and previously relatable voice as a QPOC is now being masked by her extreme performativity as she navigates this new space.

A Little Late with Lilly Singh Intro

What I personally find unfortunate about this situation, as a fan of Singh’s old Youtube channel, is how her performative behavior and the backlash against it has completely overwhelmed the narrative of an Asian American being represented on late night television, which is worth celebrating. There was and still is so much potential for positive representation on these platforms where Asian Americans have previously not broken into, and this first season of A Little Late should not put a dampener on that. Lilly Singh gained a following on Youtube through her comedic take on her cultural identity that resonated with her fans, many of whom were excited to see themselves represented in one of the top-grossing influencers of the decade. On one hand, I feel it is unfair to judge her by the same standards, seeing as her comedy and style might not translate directly onto this new platform. On the other hand, I agree with her critics and hope that, along with the other creators working on the program behind the scenes, she can grow and strengthen her voice as a trailblazer for underrepresented communities with a more nuanced approach.